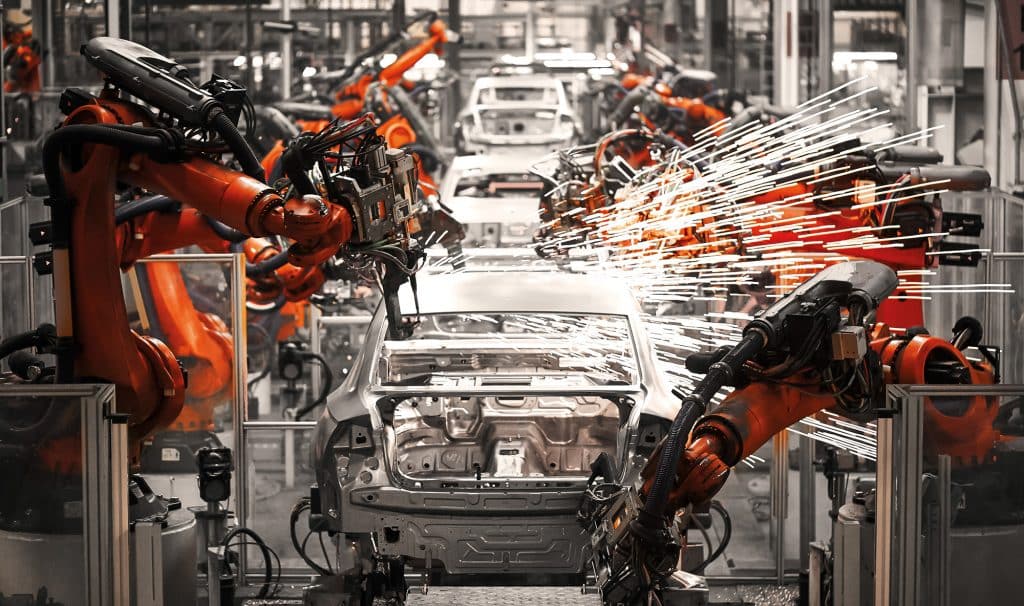

Car manufacture on the continent riddled with looming trade war seems headed for a dead-end.

Remember the good old days when the biggest challenges the European car industry faced were the oil crisis, the rise of Japanese carmakers, and disgruntled unions? Today, the car industry is fighting for its very survival as the mobility sector is transformed by new technologies.

One can forgive European carmakers for being a bit distracted by shorter-term concerns like the threat of US tariffs, slumping Chinese demand, and stricter emission standards.

Europe and its car industry are already dealing with US steel and aluminium tariffs imposed in 2018 as part of the trade war. In May 2019, the US Department of Commerce announced that foreign cars and car parts were a threat to US national security. Tariffs of up to 25 percent could be imposed, with a decision to be made within 180 days of the announcement. Negotiations behind closed doors must be frantic. EU governments are sit-ting down to agree on a unified, post-European elections approach. German car executives have already been to the US to try to reason with President Donald Trump.

Escalating trade war that involves vehicle companies

An escalating trade war would be disastrous not just because of the direct impact on demand, but also because the European car industry is a global supply chain. Cars and parts are made around the world and assembled in various countries. Tariffs will drive up costs, and may cause carmakers to relocate their production centres.

Brexit is a similar problem but on a smaller scale — and with less certainty. Already several carmakers have closed or reduced production in Britain. Honda is closing its Swindon plant, Nissan is moving some future production back to Japan, and even Dyson has moved its electric car subsidiary to Singapore.

European car makers are also reeling from a slump in car sales in China, recording 11 months of de-creasing sales by this May. Many carmakers are desperate for an improvement in the second half of the year, but there is little optimism for a quick turnaround. China became the biggest car market in 2010, and in 2017 had 35 percent of the passenger car market; the EU was the next-biggest at 21 percent, with the US following at nine percent. The slump is a major cause for concern.

To take advantage of the growing market and to meet Chinese government requirements, many Europe-an carmakers have set-up production in China, mostly with joint ventures. Volkswagen produces close to 40 percent of its total production in China, Peugeot (PSA) close to 20 percent.

European carmakers have bet big on China trying to navigate the trade war — and now they are facing the costly prospect of stricter emission regulations as well. In the wake of the 2015 “Dieselgate” scandal, European policymakers are determined to cut emissions from motor vehicles. They are proposing a 15 percent cut in average CO2 emissions for cars produced in Europe by 2025, and 35 percent by 2030. Many cities have announced future bans and restrictions on diesel vehicles, including Paris, Hamburg, Berlin, and London. This is forcing a costly transition on European carmakers — but in forcing them from diesel to electric, it may be a strategic blessing in disguise.

All these pressing concerns represent serious challenges, but European carmakers must also look ahead to other existential challenges.

Vehicle companies in 2030

By 2030, 30 percent of a car’s value will be in its software, but Europe is lacking the relevant expertise. The biggest software advances are being made in Autonomous Vehicles (AV), followed by increased connectivity. Self-driving cars will communicate with others to manage traffic, while passengers benefit from a range of new services and entertainment. High-end cars already have around four times more lines of code than a F-35 fighter jet — twice that of the CERN Large Hadron Collider.

The leaders in AV are US tech firms, notably Google and Apple, as well as Tesla and the Chinese firm Baidu. European carmakers are behind the pack, but attempting to catch-up through acquisitions and strategic alliances. Ford and Volkswagen have made an agreement to share AV technology; Fiat-Chrysler have aligned themselves to Google; Audi, BMW and Daimler (Mercedes-Benz) have bought a digital mapping company. Daimler has also been working with Uber; BMW with Intel and Israeli firm Mobileye, and Renault-Nissan has partnered with Microsoft.

Technology is changing how cars are used and could impact the trade war. Ridesharing will challenge the concept of the private car — and Europe is trailing here also. In 2017 it was estimated that 338 million people used ridesharing ser-vices like Uber, Lyft and China’s Didi Chuxin. That growth could become exponential when companies introduce AVs dedicated to ridesharing. By 2030 it is estimated that one in 10 cars will be shared. Euro-pean carmakers are scrambling to join forces with former competitors and ridesharing platforms to make up for lost ground: BMW and Daimler have merged their ride-sharing divisions, and Volvo is working with Uber.

Trade war: electrification

Another big technological disruptor to European carmakers is electrification. Electric cars are not new, but recent improvements in batteries, drivetrains and public charging infrastructure have started to make electric cars a viable alternative. China is the leader here, with 400 electric car options on the market; in Europe there are six. The biggest electric carmaker in the world is China’s BYD. China, Japan, and South Korea are leaders in battery production. Tesla has a Gigafactory in Nevada, and one under construction near Shanghai.

Europe is currently at the mercy of Asian suppliers. Volkswagen and BMW have announced plans to produce their own batteries, in co-operation with Goldman Sachs, Ikea, and a small Swedish battery pro-ducer Northvolt — but the first examples will not be ready until 2022.

The transition to electric cars will also have an impact on the workforce. Electric cars are less complicat-ed, requiring fewer workers. A typical electric engine has just 200 components; a diesel engine has 1400. By 2030, as a result, it is estimated that 300,000 manufacturing jobs will be lost in Europe. More will be lost indirectly. The industry currently employs 13.3 million people, 3.4 million of them in manufacturing.

European carmakers are feeling the pressure. The CEO of Volkswagen, Herbert Diess, recently said that the European car industry could mirror the demise of that in Detroit. That seems an extreme scenario, as European carmakers are now making swift, bold decisions. The industry has a long history, and is de-termined to have a bright future.

See more at CFI.co Blog